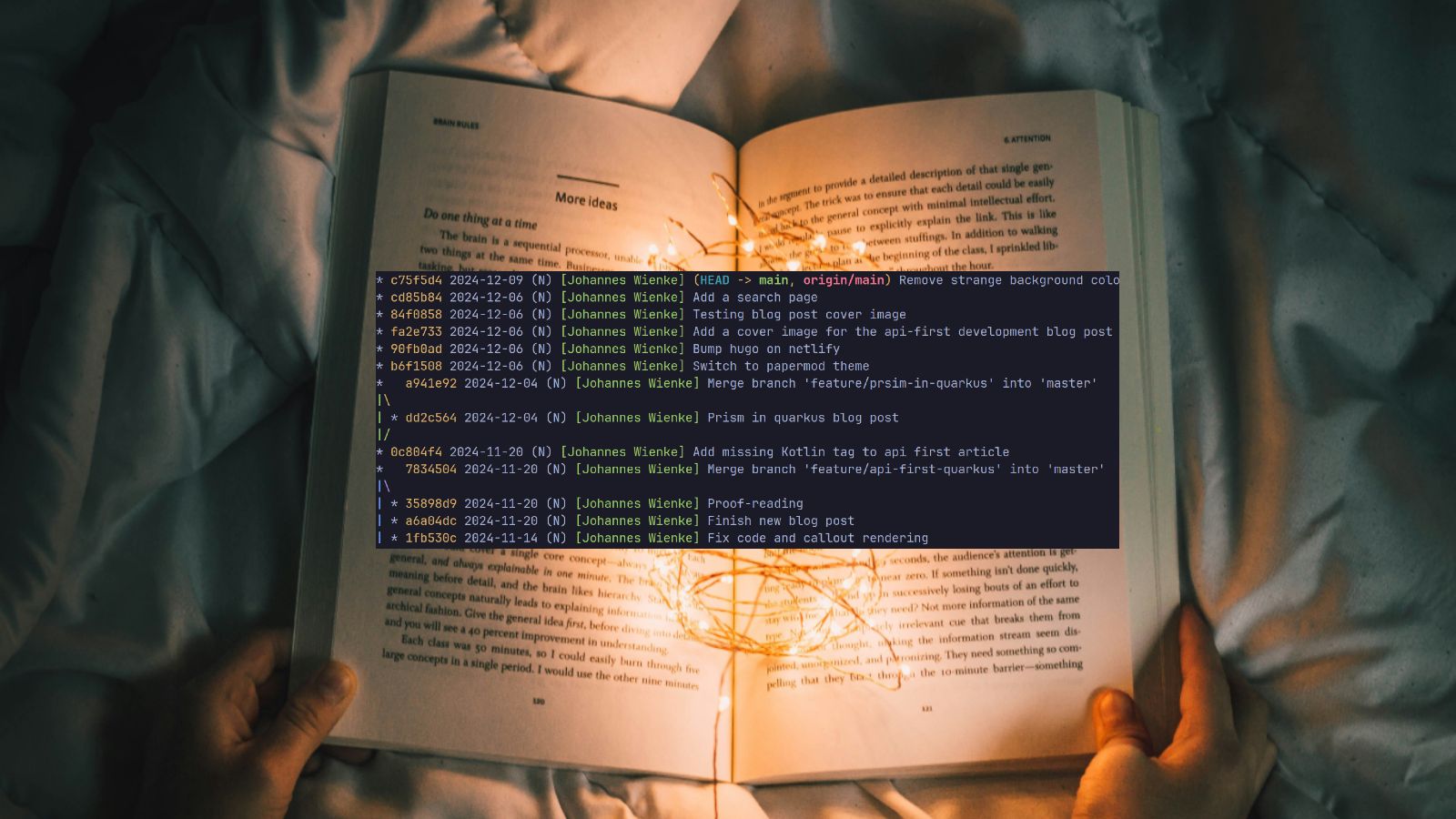

Tales from the commit log

A piece of software never exists in isolation and without context. The problem to solve and the reasoning and experience of its programmers shape the implementation and are important information for future developers. Even well-written code cannot convey all of this by itself. Therefore, further means of communicating such information are required. Code comments and external documentation are the obvious choices. However, with Git we also have the chance to design the commit log in a way that it deliberately tells a story about the implementation that is not visible from the code itself. Table of contentsWhy code and change sets need to communicateRecording history vs. telling a storyProperties of good commitsCreate cohesive commitsExplain what has been done and WHYCreating a clean commit historyBibliography Why code and change sets need to communicateProgramming is a form of human communication, mostly with other humans; incidentally also with the computer by instructing it to execute a function for us. Therefore, when implementing something we carefully need to consider how to communicate what and how things are done, similar to when we talk to each other about a manual task using natural language. We need to negotiate why and how we do things to ensure that everyone understand what to do and in which way. Otherwise, misinterpretation, confusion, and conflicts are pre-programmed. With current software development techniques such as pull/merge requests, the phrase that code is read much more often than it is written or changed is probably even more valid than it ever used to be. Reading only makes fun and delivers the required insights if the literature you are reading is well written and not a convoluted mess of illogical mysteries. Similarly, reviewing a pull request only works well if the proposed changes are presented in a way that is understandable. Clean and self-documenting code is an important technique to ensure a reasonable reading experience. However, the code itself mostly explains what and how something is realized. The really important pieces of information usually hide behind "why" questions. Why did I use this design over the more obvious one? Why this algorithm and not the other one? Why is this special case needed to fulfill our business requirements? Why do we need to make this change at all? These are actually the important pieces of information that will likely cause confusion sooner or later if omitted. Bugs might be introduced in future refactorings if business requirements and their special cases are not known to someone reworking the code. New features might break the intended design if it wasn’t clearly presented. Finally, a pull request review is much more productive and also more pleasing for the reviewer if requirements, design choices, and motivations are known. Code comments can answer many of these issues if done properly and much has been written about how to create useful comments (e.g. [Atwood2006], [McConnell2004] chapter 32, [Ousterhout2018]). Good and concise recommendations are: Comments augment the code by providing information at a different level of detail. Some comments provide information at a lower, more detailed, level than the code; these comments add precision by clarifying the exact meaning of the code. Other comments provide information at a higher, more abstract, level than the code; these comments offer intuition, such as the reasoning behind the code, or a simpler and more abstract way of thinking about the code. — [Ousterhout2018]...